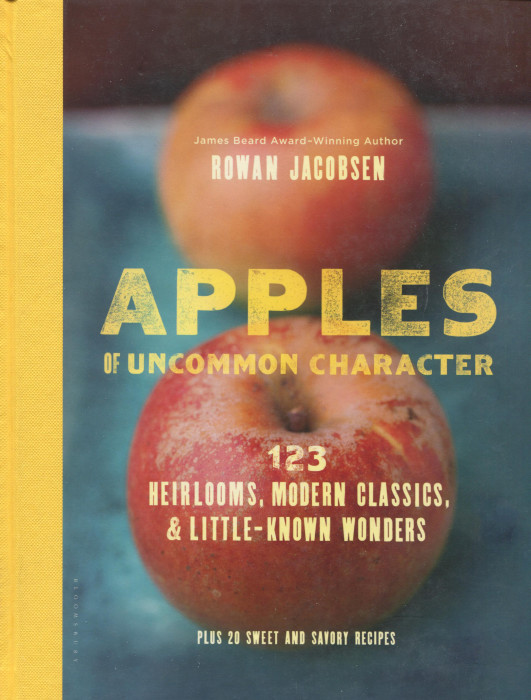

You probably eat apples — yes, pie counts! But what do you know about them? And how can enjoy them oh so much more? There is a wealth of insight and inspiration in Apples of Uncommon Character by Rowan Jacobsen. A wealth presented with great entertainment and substantial education.

I’m not sure where to put my copy of Apples, in my kitchen or in my car. Read on and you’ll know why.

The next time you are buying an apple, put down that Red Delicious and pick something else. 75% of American apples are those Reds. And most of the remaining 25% come from just these five: Golden Delicious, Gala, Fuji, Granny Smith, McIntosh.

Rowan Jacobsen is a James Beard award-winning author, for his Geography of Oysters. And he has another seven books including this new one, Apples of Uncommon Character. A few years ago, he bought a farm in Vermont, in part for its lovely meadow. In the first fall, he discovered he had apple trees as well, but trees bearing apples not like you see in Whole Foods, apples coming in a cascade of colors and flavors and textures that he had never experienced. That began his apple odyssey. He has traveled across North American discovering the story of apples and how singularly important America has been to apple culture.

In this book, Rowan spotlights 123 apple varieties. Some are the classics, some are the new wonders that come from genetic science, and some are little-known wonders that have survived extinction and are now being promoted by apple advocates. For America has proven to be the world’s petri dish for apples.

Think first of Kazakhstan. You know where it is, right? Yes, other side of the planet. There, in south central Asia, apples first appeared. They were enjoyed immediately and humans learned to propagate them. Oh, you can drop an apple on the ground and let the seeds give you the next generation of trees and fruit. But, as with many fruits, that’s a problem. Plant a seed from, say, that Red Delicious, and the tree that grows up may give you Red Delicious. Or it may not. The apple genome is big and subject to mutation on a rapid scale. If you want your apple tree to give you the “same” fruit as its ancestor, you have to graft on a branch from that ancestor. If you don’t graft, you don’t know what you will get.

That’s why, when you eat a McIntosh you owe a debt to a Farmer McIntosh in Ontario who, in 1811, identified a species of apple he liked and did the first grafted. Your McIntosh comes directly from his tree.

No, most of the genetic variations are not wonderfully edible raw or in pies. It takes time and talent, and perhaps some luck, for humans to find a tree that gives something we’ll love to eat. Today, there are teams roaming around, looking for stray apple trees, trying their fruit and adding to the catalog of heritage apples that we now crave. Down your street, there may be a 200 year old treasure house of flavor, waiting for discover. And for grafting.

Now, this grafting need holds for many fruits. But apples have one very special feature: they are hardy as the devil. If left untended, other fruit species will wither away. I takes humans to keep them thriving in abundance. Apple trees are different. They drop their apples and new generations appear, generations with very different characteristics. Birds and bears and deer perform yeoman work in spreading the evolving species.

Apples were not found in American before the Pilgrims. By the late 1800s we had over 16,000 species [well may about 7,500; the number is disputed the enormity of species is not]. Humans helped much of that spread, but it was also the bird and bees and bears.

Apples has chapters devoted to apples by category of best usage:

Summer Apples ripen at a swift pace and quickly reach a peak for eating. They are not for keeping for the fall pie season. Eat them now for tomorrow will be too late. Examples include the Ginger Gold and Gravenstein.

Dessert Apples can be enjoyed on their own, possess a thin skin, and are typified, if not dominated, by the Honeycrisps.

Bakers & Saucers are apples that have so much cellulose they are almost too crunchy when fresh, too much of a fight when you bite. But that means they do not “water down” when you cook or especially bake with them. Here you will find apples like the Jonagold, introduced in New York in 1968 as part of the ongoing apple research that began 1890 at Cornell University.

Keepers are apples that, like wine, age well. Today, with controlled storage keeping oxygen away so that those Red Delicious can appear year round, we don’t appreciate that there are other species that have a natural ability to store and preserve flavor and texture. You may not have ever seen an Arkansas Black but you might try to search one out.

Cider Fruit is devoted to apples that make the best in cider. America is hot-bed of beverage making these days: gin, bourbon, beers and surely ciders. Here many of the best species come from Britain, but you might be able to find a Hewes Crab, originally developed around 1700 in Virginia but now found in the Hudson Valley.

Oddballs is the chapter devoted to apples with odd histories, ugly outsides, or cuteness that cannot be denied. The Hidden Rose, from Oregon in the 1960s, looks when cut like a watermelon, not an apple at all.

Apples concludes with a Recipes chapter that will tempt you for every step of the meal:

Apple Pakoras with Yogurt-Mint Chutney

Grilled Apples with Smoked Trout, Fennel and Lemon Zest

Chicken Curry with Apples and Onions

Maple Applesauce

Apples and Oranges Galette

Apple Pie Squares

For most of my life, I have lived in apple territory. In Oregon, we had Hood River apples and of course the apples from Eastern Washington, the biggest apple orchards in America, if not the world. Now, Suzen and I live in the Hudson River Valley, both in Manhattan and near Kingston a hundred miles north. The apples first appear in mid-summer and then peak in the fall. In October, each farmers market smells more of apples than falling leaves.

Which leaves me wondering where to put my copy of Apples. I can leave it in the kitchen, for now, looking at each chapter and wondering if somewhere local I can find one of the classics — old or new — described in the book’s chapters. But surely by mid-summer, the book has to be in my car. When Suzen and I go from one farmers market to the next, we want to be able to see what heritage apples are in the stands and hopefully to read one of Rowan’s surveys for that particular variety.

There is an almost genetic rush now to discover and enjoy apples. There is a serious industry devoted to heritage apples and to inventive ciders. Apples are integral to our food culture. And Apples of Uncommon Character is surely the best way for you to learn and become happily involved in your own private apple odyssey.