This is a lovely and important book.

Now, I know what you are thinking. British cuisine? Isn’t it, well, you know rather not terrific? Stop it. Stop it now. You need some tolerance and some curiosity. And when you absorb this book’s lively history lesson, your entire attitude will change. We have underrated and underappreciated the diversity of British cuisine. And, that cuisine continues to evolve, often in gigantic steps.

My last name is O’Rourke, but I am only half-Irish. The rest of me is Scotch and English. My Scotch-English grandmother lived with us and cooked for us every day. We had roast beef, Yorkshire pudding, calves’ liver, and curries. Plus gingerbread in cakes and cookies.

It was pretty good food. I learned to have a Pepsi close by so the curry would not burn. And I always scrambled for that end slice of the roast beef.

This book puts British cuisine in perspective. It is not that British food is just “not French.” There was always inherent British food. But we all have too much of a London perspective. London has been there for over 2,000 years: rich, big, and central. The rest of Britain is further north, colder, poorer, and filled with people who learned to scramble for their meals. We think of the richness of the British Empire, but that wealth was not spread evenly across the land. With uneven resources, you could only expect a diverse cuisine. Rich dishes for the London crowd, and those at the top of the heap in the industrial cities. And for the rest of the population, life was harder and more demanding.

As living standards rose, many of those “poorer” dishes have been lost or forgotten. In this book, some of them appear again and do so with appeal. Simple or modest can still be delicious.

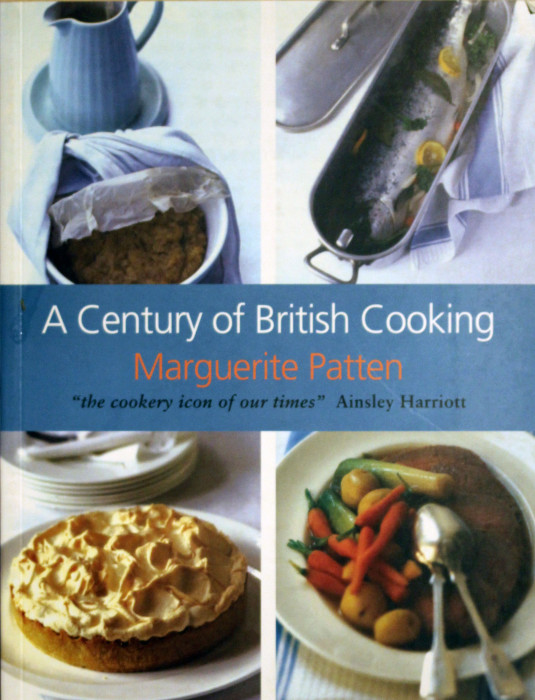

The author of this book is singularly qualified to write it and comment on the thrust of British culinary evolution in the past hundred years. Marguerite Patten is 98 years old and has been teaching cooking since the 1930’s. She written 160 cookbooks with sales of over 17 million copies. There is no one like her. She is, I think you’d concede, an expert. The expert.

The author is 98, so the book must look a bit old and … No, Marguerite is clearly still hip and the publisher, Grub Street, surrounded her with a marvelous production team. This is a lovely modern looking book with a layout that is web-influenced but still shows all the hallmarks of superior publishing. The paper, ink, fonts, and page layouts give this a book a strong visual appeal and easy readability. It’s an easy, fun read.

The book is divided into chapters that walk you through the 10 decades spanning 1900 to 2000. Each chapter has two parts: background and recipes. It’s that background part that will appeal to any foodie. What was life like in the Britain? What was a typical kitchen like? What foods were available, depending on your class in life [and we all know from Downton Abbey that class mattered]. What prepared foods could be purchased, what were the favorite drinks, and what were typical meals from breakfast through dinner? What were the cookbooks of each decade that aided and inspired home cooks?

And the recipes? What were typical recipes decade by decade? In that chaotic 20th century, Britain began as the most important and richest country in the world. Then came World War I, the depression, the trials of World War II, the years of recovery and rationing, and then the ups and downs many of us recall from the 60’s on. British stature and life has changed. So have the recipes.

There is a charm to reading what was typical in the first years of the 1900’s. There is Windsor Soup, with a calf’s foot and beef bones and Madeira. There’s Lamb and Mutton Cutlets and Pulled Rabbit — just like pulled pork, folks.

When World War I began, the cooking changed. Stale bread was used, not thrown away, in Snowden Pudding made with marmalade, citrus juices and citrus zest. Sugar was rationed, so Condensed Milk Fruit Cake evolved. Marguerite remarks that, still and always, the cake is remarkably pleasant in texture.

After the War, the 1920’s saw recovery. And simpler meals and dishes. Chicken was always sold with the giblets so Giblet Soup became a staple for the middle and lower class. When food rationing finally ended in 1921, people did return to some of the richer Victorian and Edwardian dishes, like Chicken, Veal and Ham Pie. The recipe is here and you might try it, just to get the feel for “being Victorian.” There’s a casserole dish, Lancashire Hotpot, that could have varying amounts and qualities of meats, depending on a family’s fortune. And, the dish could be taken to the local baker to be cooked there in case a family did not have a stove of their own. That seems peculiar now, but it was common across the poorer stretches of Britain.

The 1930’s can only be described as hard. So you find Mock Fish Cakes: potatoes and beans cooked with lemon juice and anchovy paste to create that “fish” sense. Shepard’s Pie was served on Tuesday or Wednesday, using the leftover meat from Sunday’s big meal, if a big meal was to be had. Even in the 1930’s, many homes did not have stoves. Only 25% had refrigerators. And here you will find still another recipe for the ever present Coffee Walnut Cake; although here Marguerite offers a funny note: the cake now called for an American-style frosting [Southern frosting really] that British homemakers found intimidating.

The 1940’s were about survival, not food. Canned milk, powdered eggs, canned corn beef and Spam. All you could do is pray for the war and then the rationing to end.

Let me leave you here is history. The story beginning with 1950’s evolves and builds. It is happier and you’ll find lovely recipes here:

- Calves’ Liver Pate made easier when aluminum foil arrived in 1966

- Cheese Fondue with those lightening bright fondue pots of the 1960’s

- Chicken Maryland [Fried Chicken] with introduction of deep fryers in the 1970’s

- Water chestnuts and bamboo shoots as the world economy expanded in the 70’s

- Beef Wellington for the masses with puff pastry in the supermarket

- More wine as the bar opening times changed in 1995

- Everything Asian as immigrants and airplanes brought the world to local streets

This book is a marvelous survey of how much and how fast a food culture can change. I do encourage you to pick up a copy for the details from 1950 on. It’s a fascinating story, and it just may make you appreciate living in the here and now.

The only drawback to this book? Where is Marguerite’s history of the past century of American food? I don’t want to impose on someone who is 98, God knows she deserves some rest, but we really, really need the American soul mate here. And I would not want anyone but Marguerite to supply all the fun and detail and wisdom.