There are visual monumental moments in your life — those instances when you see something so astonishing that decades later the vision has barely faded. You can close your eyes and be right there in the spot again.

A dozen years ago, Suzen and I were attending a cooking school in Tuscany, the very wonderful Toscana Saporita taught by Sandra Lotti:

Half the day at Toscana is spent in the kitchen and half on food tours throughout the hills, shores and yes mountains of Tuscany. We were on one of those mountain roads, miles away from pavement. The road was steep and the tires were kicking the rocks around like a private avalanche. Back in the hills, the autumn day has been pleasant. Up high now, the air was cold and the van was too chilly despite the dozen of us huddling for warmth and to avoid the jolts of the one lane that seem to spiral ever upwards.

When we got out, it was a cloudy day, near the top of our mountain. There was a purple ridge line a mile away and before us an old, old building whose roofline seemed to mimic the mountains: up, down, forward, back. It was the tallest one story building I had ever seen. Dark wood with stone randomly built into the walls here and there.

Inside, the wood was darker and Suzen and I had to wait for our eyes to adjust. There were a few windows and the dusty panes let in a flood of late afternoon yellowing light. The light beams crashed through a maze of rafters, wood pieces assembled like a jigsaw puzzle. And from every rafter, at every angle, there were strings and ropes supporting a circus of salumni. Dry-cured meats of every size and description hung down with just a touch of gravitational menace: some almost as small a pencil and some so humongous that it would take two men to wrestle the beast to a cutting station on the ground floor.

We only spoke English. They only Italian. But they had a vocabulary of smiles and gestures, nodding to us, beckoning, suggesting. We sampled their wares, some from the cabinets on the floor. Some from items they happily climbed up a ladder to retrieve and then gracefully sliced and present to us.

I ate more meat than ever before in my life. It was an experience I can’t forget. My only regret is that I ate in ignorance.

Now, I can resolve my dry-cured meat education.

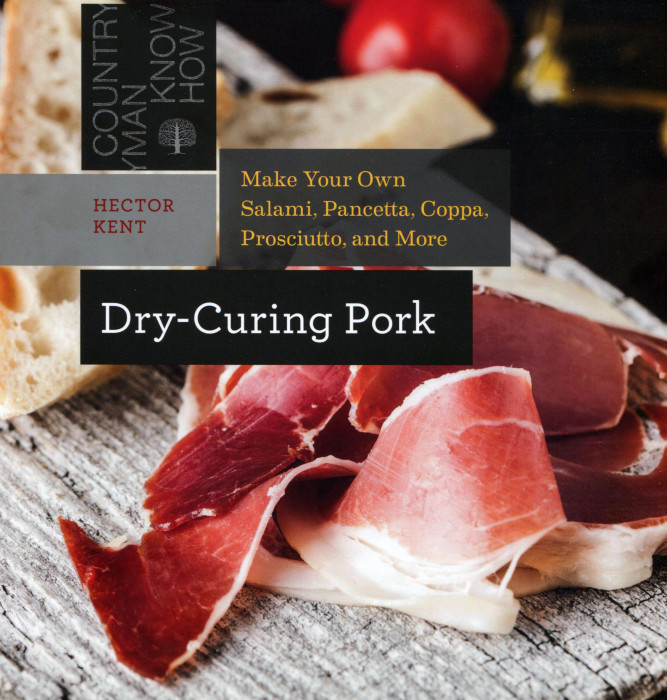

Dry-Curing Pork by Hector Kent is the definitive English guide to understanding what dry-curing is and how, if you desire, to do it yourself. Hector is a biology teacher whose fascination with this cooking technique began in Oregon and continues now that he lives in Vermont. With his wife cutting meat at his side, Hector has mastered the centuries of science and art that make dry-curing one of man’s most complex cooking traditions.

When you cure meat, you transform it. And then you cook it. When you dry-cure, you transform it, but then you do not have to cook it. Dry-curing is accomplished with salt and then perhaps sugar [and spices] and possibly with cold smoking. Cold smoking is accomplished at 90°F or less — no intense fire or billowing smoke, just wispy fumes and time.

You can dry-cure many meats, but this book focuses on Hector’s passion: pork. The book has three principal sections:

The Art of Dry-Cured Meats is a Master’s Degree in the chemistry and principals of curing. The goal here is to reduce the water content of the meat — the total weight of the meat is reduced by 30% — so that bacteria cannot form and destroy the meat. You don’t eliminate the water, but you use salt to restrict the chemical reactions that take place. Good bacteria are encouraged. And good mold may form on the outside.

The process varies depending on the meat you are employing. It may take a few days. For a big ham, a year is essential and up to three for a superior experience. Along the way, you’ll need to monitor temperature and humidity and even the light. There is nothing quick here while the technique are ageless.

Teaching Recipes takes you through the art of preparing a half dozen items, ranging from coppiette to pancetta to carnitas. There are pages of detail, all quite necessary for your curing success. Hector has written this book for those of you who want to take up curing as an intense hobby or pastime. He just lets you know that there are hours of prep work and study, and then weeks to months before your first product is ready. This is not Twitter-food in 140 characters or less.

The final section of the book — chapters devoted to Whole-Muscle Dry-Curing, Salami, and Mediterranean Dry-Cured Hams — have recipes of equal quality but with a little less detail. By the time you have graduated to these ideas, you will have mastered all the concerns and twists that dry-curing entails.

Who should read this book? Well, clearly, if you have cleaned out a section of the basement, bought salt and are ready to cure away, then this is the guide for you. Not all of us have the space or the patience for home curing, but it is a trending scene. There were far fewer of us making beer at home a decade from now. Perhaps in 2025 we’ll consider “home ham” to be as common as that “home lager.”

Second, if you aren’t going to do this yourself, but you want to know how to buy and to understand what to buy, then this is your pocket guide to dry-cured meats.

Lastly, if you are planning a visit to Europe, particularly to Italy, then here’s a book to read on the plane, and then take to the market or to your restaurant. You can open the book, point, looking with pleading eyes and I’m sure some intelligent waiter — proud of centuries of culinary artistry — will do his best to please you. Sample a few of the thousands of regional specialties, and, who knows, you end up making your own salami. That’s why Dry-Curing Pork was written.

I just received my copy of Hector Kent’s book and a cursory once-over indicates it will provide quite a bit of useful information. However, I spotted one statement in the book that is very disturbing: on page 24 there is a suggestion that Cure #2 and saltpeter can be used interchangeably. Anyone following that suggestion could end up using either about 15 times more or 15x less nitrite/nitrate than is required for safety. A dangerous situation!

Thank you for this safety issue. I’ll try to contact the author.