Coincidences happen. I picked up Wednesday’s New York Times because Wednesday includes the weekly Food section, a must for foodies living in NYC or anywhere else on Planet Earth. Right there on the front page of Food, there’s a big picture of Korean food with the headline Kimchi Travels Well.

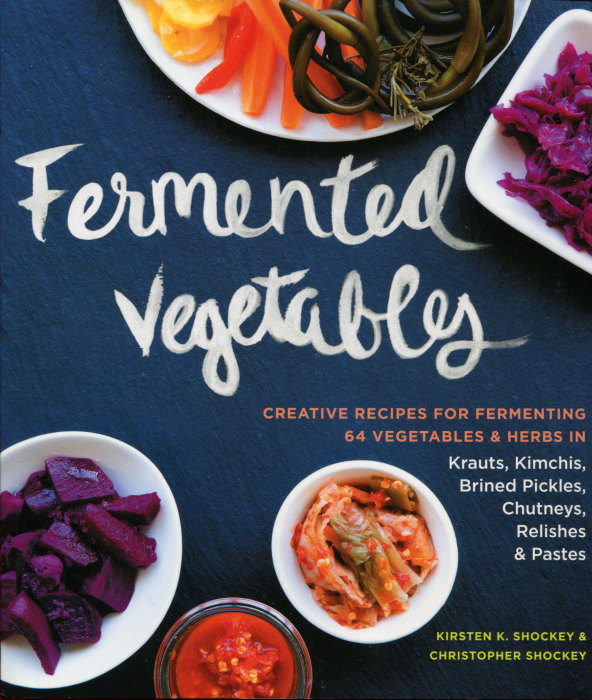

Back home with my coffee, I’m reading The Times and finishing off this review of Fermented Vegetables by Kristen K. and Christopher Shockley. A third of Fermented Vegetables is kimchi, lots and lots of kimchi, dozens of different kinds of kimchi. So, the Shockeys must have lived in Korea or traveled there or, names aside, be 100% Korean, right? No, they own a farm in Southern Oregon. And they have never been to Korea. But they are into kimchi.

Their farm lies in one of the most verdant areas in the nation. They sell their farm products. Along with lots of other farmers, which introduced issues of competition at the local farmers market. The Shockeys may not be Korean, but they know one key lesson from marketing: differentiate yourself. So, instead of selling produce, they began to make fermented food products, pickling vegetables and fruit, experimenting with sauerkraut and kimchi.

They have become experts, very technical experts, and Fermented Vegetables is their tome devoted to every possible aspect of fermenting food items.

There are pickles here, of course, but so much more. Section 3 of the book covers ways to ferment almost 80 vegetables and fruits — ranging from arugula to zucchini. Not just carrots and cucumbers but also celeriac, chard, cilantro, peas, garlic, rhubarb, sweet potatoes, and tomatillos.

Those recipes are preceded by 100 pages covering the fundamentals of fermentation and then details for kraut, pickling and kimchi.

There is no vinegar in this book. None. It’s all about salt. The recipes here deal with fermentation that occurs when food products are buried in a salt brine and natural bacteria go to work in the absence of oxygen. The ideas for kraut, pickling, and kimchi represent three different techniques.

Krauts, typically made with leafy vegetables like cabbage, are built from just the veggie and salt. No water. The veggie is cut or shredded, breaking apart some of the cells and releasing some natural liquid. Adding salt and mixing intensifies the production of liquid and results in a brine that covers the original veggies. A crock pot — and nothing made of metal or plastic — is used to store the kraut while the fermentation transforms the food. In a matter of days — for a small batch — or a few weeks — for a large batch — you have kraut. Some of you may have memories, or tales from your grandparents, about the kraut barrel that sat in the basement all winter long.

How to select that crock pot, keep the top from being forced off, and how to judge doneness are among the topics the Shockeys cover with expertise.

The second technique is pickling, which can produce pickles of course. But pickling works with other veggies, too. Here the idea is not to shred or cut the food. The whole veggie, or big chunks, goes into the container. Here both salt and water are added. The water must be pure. The salt should be distinctive. And, the Shockeys point out, the salt should NOT be pickling salt which, desire the claims of purity, contain trace chemicals for preservation purposes that contaminate a pickled product.

For the prototype, pickled cucumbers, the Shockeys go into massive detail. Ever made your own pickles and been disappointed: the pickles were wimpy and flopped around, or they were touch as jerky? Wrong proportions of water and salt. The Shockeys walk you through it with confidence.

And lastly we come to that kimchi category, the front page item in today’s Times. You may think that kimchi is cabbage, and it can be, but there are over 200 kinds of kimchi made in South Korea where the average person eats 40 pounds of kimchi a year. That’s just under a pound a week. Every tasted kimchi? It’s beyond hot. Beer can barely contain the fire. A pound a week? Do not mess with a Korean.

Kimchi is made by combing the two early techniques. The veggies are shredded to release natural juice, but water is still added. The pot goes to the side. Bacteria goes to work. In a few days, you have a food that any Korean would love. And you may, too, beer in hand.

Fermented Vegetables is an exceptionally detailed book. It’s not a light read. It’s a textbook. And, yes, it is still a cookbook. Somewhere in the mega list of veggies, from A to Z, there are items you’ll want to experiment with. Fermented cilantro? There’s something to put in soups and stews or use like horseradish on top of a roast beef sandwich.

There are more ideas here than you could begin to do in one spring and summer. If you love pickles and are intrigued with making your foods your way for yourself, then this is a book you will enjoy for years.

The book concludes with 84 recipes for breakfast through dessert using fermented products. You’ll find Smoky Kraut Quiche, Fish Tacos, and Zucchini Muffins. And there are Crocktails: cocktails made with the left over brine. Like a sour drink? They are here with a pucker factor you surely have not experienced.

I’m happy to recommend Fermented Vegetables as a lovely, serious book that fermenting foodies will devour, one sour bite at a time. Or one sip!