There is something about that first crocus of spring. One day the ground is covered in snow. The next in hard brown earth. And then this little trooper just shoots up for too few days of glory.

I had to use Photoshop on this picture to take out the snow just to the side. If Suzen saw one more flake, well, it’s been a long winter.

Spring and then summer and then fall. Fresh food. Fresh fruits. You can see them now in your store, although here in New York they all have “Made Somewhere Way South” stamped on the cartons. But in a mere seven weeks, our local farmers markets will begin and our local berries will begin to appear.

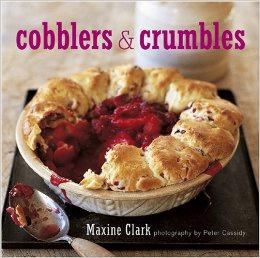

I am indebted to the book Cobblers and Crumbles by Maxine Clark for the content here. She’s English. So are the cobblers. I like a cobbler dessert. It’s a breezy fast way to adorn fruit with a pastry topping and rapidly have a fiery hot dessert, perhaps tempered by homemade vanilla ice cream. Cobblers can absorb the whole range of fruits about to burst upon us: berries, peaches, apples, pears, … In her book, Maxine even has a Rhubarb and Orange Crumble to use that tart spring rhubarb.

Oh, she calls that one a crumble, not a cobbler. And in fact you can make cobblers, crumbles, slumps, grunts, pandowdies, buckles, betties, and even something called a sonker [although you probably have to live in North Carolina to have heard about that one].

What’s what? Is there really a difference? Yes, there really is.

The cobbler is the basic dessert. A fruit base in topped with a biscuit topping that gives the dessert a cobblestone appearance.

In a classic crumble, the topping is a single sheet of streusel made with only flour, butter and sugar. Unless, as in countless recipes, you add oats or nuts in some form. The crumble is definitively British. Americans call it a crisp. And to intensify that crispy taste, you can simply add more sugar. If you add extra butter, the butter melts and you truly have one continuous topping.

In the buckle, berries are folded in a cake batter, then than batter is topped with come crumbling topping. In some recipes, the buckle cake is put on the bottom, the fruit on top, and the cake rises and buckles during the cooking process, snagging fruit chunks along the way.

The French clafouti differs in richness: the topping is a sweet custard poured over the fruit which then permeates down through everything.

In the Betty, as in Brown Betty, there are two layers of pastry with the fruit nestled safely between. If you don’t think there is ever enough pastry, then the Betty is your route to satisfaction.

Grunts are made very differently. They are not baked. The fruit is cooked separately on the stovetop and the biscuit topping is added only when the fruit has begun to steam and fall apart. That steam is what cooks the biscuit and gives this dessert its name, from the sound of the steam rising as the biscuits bake. Served on the plate, the dessert does not generally have the integrity to stand upright. It generally leans to one side or the other. That’s why grunts are also known as slumps. This is an American dish where cooks, with less complex kitchens, attempted to recreate the classic English fruit pudding.

The pandowdy has an arcane way to get that cobbler topping. The fruit is covered with a rolled out pie crust and baked. Only just before serving is the crust broken into pieces, resembling the texture — but not the depth — of the cobbler biscuit.

So, you have a bushel of choices before you. You have months and months to try all these delightful, clever, and imaginative ways to combine fruit, sugar, and pastry. If you have the mind, you can create your own. It’s a tradition that spans centuries and continents.