From the Wikipedia topic “Glass”:

Glass is an amorphous (non-crystalline) solid material. Glasses are typically brittle and optically transparent.

The most familiar type of glass, used for centuries in windows and drinking vessels, is soda-lime glass, composed of about 75% silica (SiO2) plus Na2O, CaO, and several minor additives. Often, the term glass is used in a restricted sense to refer to this specific use.

In science, however, the term glass is usually defined in a much wider sense, including every solid that possesses a non-crystalline (i.e.,amorphous) structure and that exhibits a glass transition when heated towards the liquid state. In this wider sense, glasses can be made of quite different classes of materials: metallic alloys, ionic melts, aqueous solutions, molecular liquids, and polymers.

When was the last time you ate some glass? It might have been years ago, although you now have an increasing chance of eating glass if you attend an upscale event catered in an avant guarde style. Perhaps as a kid glass was a favorite of yours at a county fair or circus. I’m talking about cotton candy. Which is nothing more than a sugar glass.

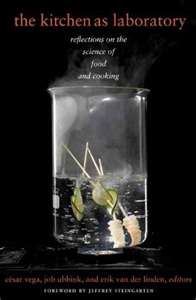

That culinary insight, if not shock, is from Chapter 24 [Sweet Physics: Sugar, Sugar Blends and Sugar Glasses] in a wonderful new collection of science essays: The Kitchen as Laboratory edited by Cesar Vega, Job Ubbink and Erik van der Linden.

The editors are food scientists par excellence. I recently heard Cesar speak at the 92Y branch in Tribeca. He is, by the way, a research manager at Mars Botanical, a division of Mars. Caesar discussed this book including the chapter on his own passion for the science of cooking egg yolks. He displayed plots of egg yolk viscosity versus cooking time, parameterized by temperature.

Okay, in real terms, Cesar has solved this problem. You want a soft-boiled egg with the yolk having the consistency of Hershey’s Chocolate Syrup. And you want it quickly. You tell your waiter, he tells the chef, and the chef looks at Cesar’s plot. The chef knows what temperature to cook at, for what time, to make your order come true. As IPads hit the kitchen, it is not too farfetched to see this actually happening.

The Kitchen as Laboratory is a great read, certainly for all geeky foodies, and even for just regular foodies who want to understand more about what happens over the stove and in the refrigerator. Food Science is not easy, but there is great progress underway, and the 33 chapters in the book — written by outstanding authorities from around the worlds — give you short glimpses into some of those enlightened pathways. The chapters include:

- The Science of a Grilled Cheese Sandwich

- Mediterranean Sponge Cake

- Spherification: Faux Caviar and Skinless Ravioli

- Moussaka as an Introduction to Food Science

- The Perfect Cookie Dough

- Bacon: The Slice of Life

- Maximizing Food Flavor by Speeding Up the Maillard Reaction

- The Meringue Concept and It Variations

- Why Does Cold Milk Foam Better

- Egg Yolk: A Library of Textures

- Taste and Mouthfeel of Soups and Sauces

You can skim this book essential facts or read it, study it, to glean very keen insights into how cooking works. It may not solve all of your cooking questions for you, but it will certainly deepen your appreciation for the magic of the kitchen.