It’s June 6, the 75th anniversary of the D-Day invasion of France in World War 2. On that day, 125,000 mostly British and American troops undertook the greatest sea invasion in history. D-Day is the true example of British-American closeness.

American began as British colonies. Then we found a Revolutionary War with them, followed by the lesser War of 1812. During our Civil War, Britain sided with the South, demonstrating a growing concern for the economic power of the Yankee North.

By the late 1800s, Britain realized its future was entwined with America. They could not compete with us but they could collaborate. No longer was the burden of Protecting the Seas dependent on the British Navy. Now working with the United States, the world could be made safe for democracy.

That happened in World War 1 and had to be repeated in World War 2.

Our social and military histories are linked to the utmost details. And that includes our culinary histories. Yes, America has influences from around the world: French, German, Italian … But at our core, our culinary foundation is British.

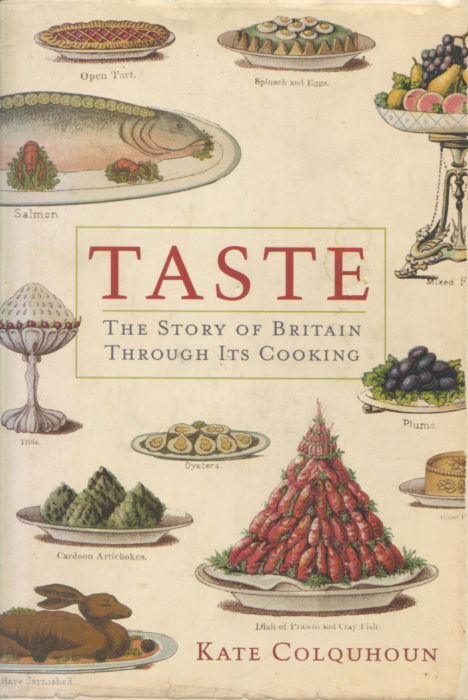

In 2007, Kate Colquhoun wrote this important tome: History, The Story of Britain Through It Cooking.

American don’t know their own history very well and it only spans 400 years or so. Britain has 2000 years of history, yet Kate navigate it one era at a time: pre-Roman, Roman, the age of Viking raiders, Medieval Britain, the Tudors, the Stuarts, and on and on. I don’t know British history, I must admit. So, I’m going to have read about The Restoration, the Victorians, and more. I do know all about Downton Abbey.

I have dipped into this thick book, reading about the Tudors and Henry VIII. Kate has a chapter there called “Strange Vegetables, New Tastes.” Henry preferred smaller dining rooms to massive medieval food halls. So in his two story mansions — bedrooms above privies — those bathrooms became kitchens, often multiple kitchens with some residences having 17 kitchens.

Henry led a change in the culinary landscape. Fiercely anti-Catholic, he reduced the number of feast days and the need for fasting. So, he drove a transition from fish to mutton. The steward of the house was in charge of purchasing all the meal ingredients and the drive for mutton soared. There were large roasting cellars, including some to hold 80 gallon copper pots filled with meat and veggies stocks. Veggies replaced spices from the Far East.

As fish declined, corn from the new world was embraced. And chocolate, pineapple, turkey, pumpkins, potatoes, red and green pepper. Plus olives from Greece and capers from Southern France. All these changes were happening just four or five decades after Columbus discovered the New World.

While we think of those early post-Columbus years as dominated by the Spanish, Taste shows that Britain was no slacker. The British explored and exploited. The Tudor history here is just one clever snapshot into Britain’s two thousand years of culinary adventures.